Special thanks to those who have recently subscribed!❤️

Welcome to Issue 6 of Becoming Berkshire, where we give a year-by-year account of Berkshire Hathaway from 1962 to the present.

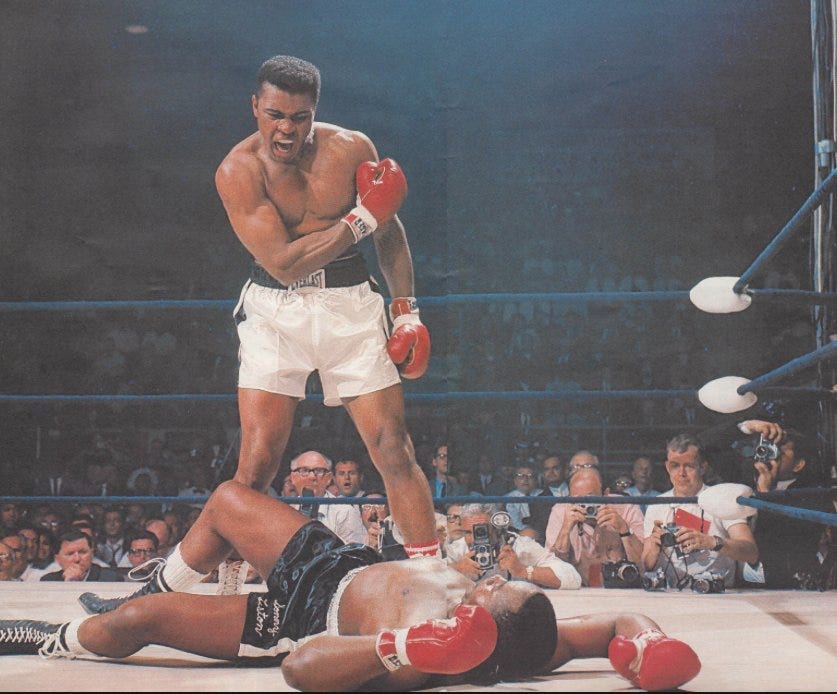

The year is 1964; Lydon B. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater in a landslide victory to secure the Presidential Election. The 24th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, prohibiting poll taxes in federal elections. U.S. military forces launched attacks on North Vietnam in response to an alleged attack on a U.S. destroyer off the Vietnamese coast. Anchorage, Alaska, had a 9.2 megathrust earthquake, which remains the most powerful earthquake recorded in the United States. Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) defeats Sonny Liston to win the heavyweight boxing title. Disney released Mary Poppins, nominated for 12 Academy Awards and the year's highest-grossing film. Jeffrey Preston Bezos was born in New Mexico, and the Dow Jones returned 18.7%.

All this happened while Warren Buffett toiled away on his partnership and continued to build a stake in Berkshire Hathaway and American Express.

Our General category now includes three companies where Buffett Partnership Limited is the largest single stockholder. These stocks have been bought and are continuing to be bought at prices considerably below their value to a private owner. We have been buying one of these situations for approximately eighteen months and both of the others for about a year. It would not surprise me if we continue to do nothing but patiently buy these securities week after week for at least another year and perhaps even two years or more. What we really like to see in situations like the three mentioned above is a condition where the company is making substantial progress in terms of improving earnings, increasing asset values, etc., but where the market price of the stock is doing very little while we continue to acquire it. This doesn't do much for our short-term performance, particularly relative to a rising market, but it is a comfortable and logical producer of longer-term profits.

In 1964, Buffett had yet to seize control of Berkshire Hathway. Therefore, I will pay closer attention to the Buffett Partnership Limited (“BPL”) shareholder letter. The letter touched on various topics, such as Institutional Management Performance, Compounding, Investment Strategy, and Taxes.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Becoming Berkshire to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.