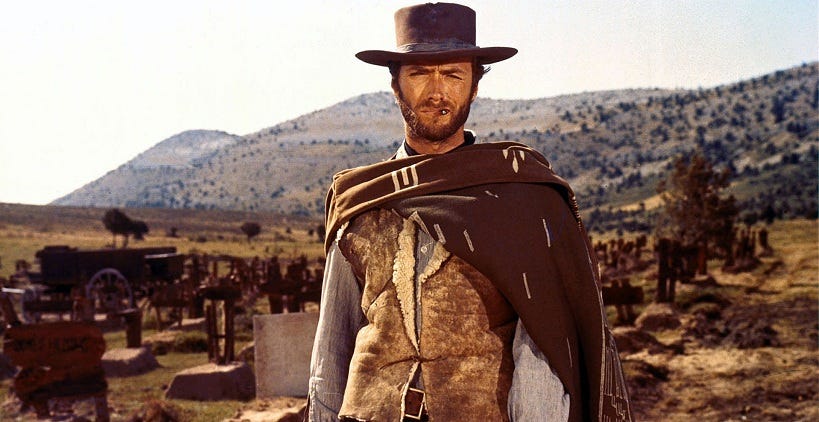

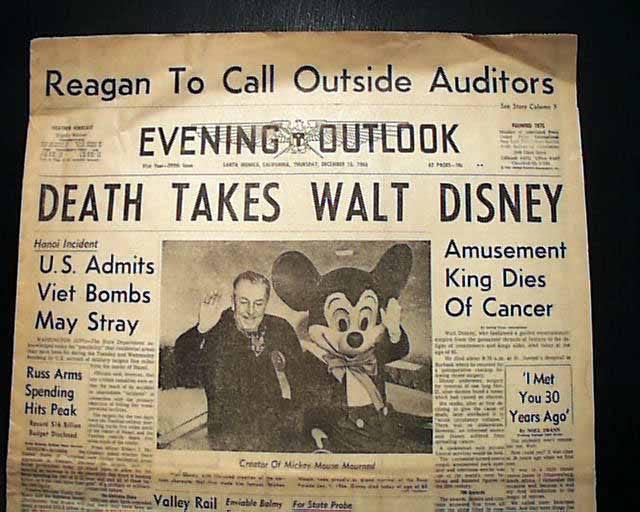

The year is 1966, and the U.S. now has 500,000 troops in Vietnam; as the war continues, American deaths increase, and the anti-war movement grows across the country. Batman and Star Trek make their television debuts. America experienced its first modern mass shooting in 1966 when sniper Charles Whitman shot and killed 16 people from atop a tower at the University of Texas. Clint Eastwood stars in his iconic Italian spaghetti western role, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. General Motors, Standard of New Jersey, Sears Roebuck, Dupont, U.S. Steel, Aetna, American Telephone & Telegraph, and Bank of America are the largest companies. And on December 15, Walt Disney passed away from cancer.

On January 18, 1966, the Dow breached the 1,000 mark for the first time, peaking at 1,000.50, but it failed to hold and closed lower. The Dow would end the year at 762.95 and not finish above 1,000 until 1972.

Having just taken control of Berkshire Hathaway, Buffett had a hectic year. He became more familiar with the Company, took a 4% position in the Walt Disney Company, and partnered with Charlie Munger for the first time on a business venture. Please note that 1966 will be broken up into two issues as we have much to cover.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Becoming Berkshire to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.