Becoming Berkshire: 1969 - Buffett Retires

Issue 13 - Part 1| Warren Buffett dissolves his partnership as he begins to focus more on Berkshire Hathaway.

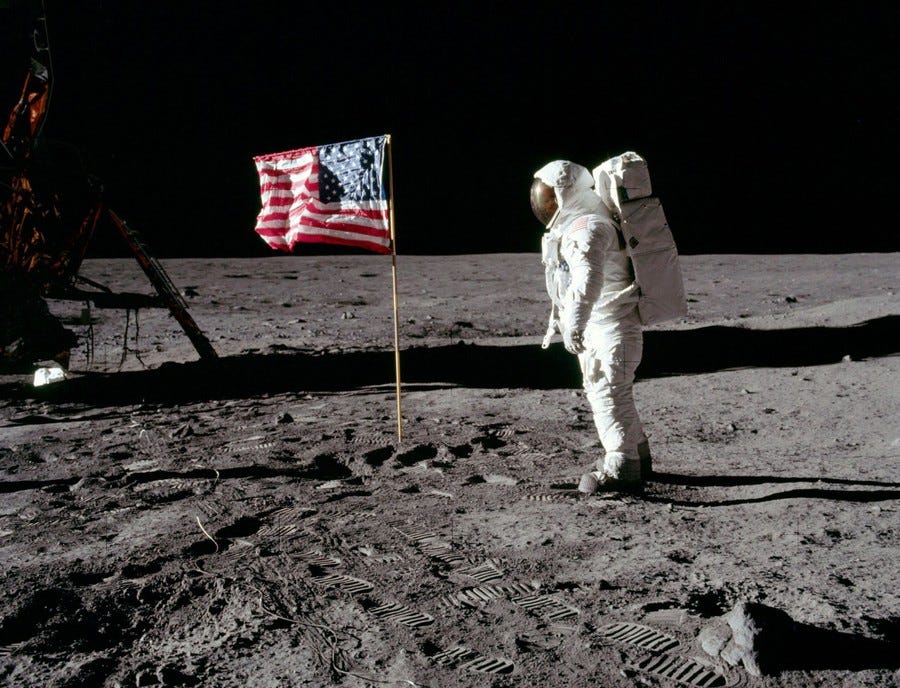

That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind. - Neil Armstrong

In 1969, Neil Armstrong became the first man to land on the moon. Boeing's 737 Jumbo Jet made its maiden flight from Seattle to New York. Charles Manson went on a killing spree, Sesame Street premiered, and Buffett retired from managing money.

Turning to monetary policy:

Despite …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Becoming Berkshire to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.