The Washington Post

Issue 25 | 1973 Part 3- Warren Buffett Invests in the Washington Post Company

Welcome to Part 3 of 1973 and Issue 25 of Becoming Berkshire.

Over two years ago, I began a journey to document the history of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett, and Charlie Munger. That journey began on December 12, 1962, when the Buffett Partnership started buying shares of a struggling textile company in New Bedford, Massachusetts, for $7.50 each.

Today, I’ve made it to the year 1973, and there’s still a long road ahead.

Thank you to everyone who’s supported me along the way, whether by subscribing, liking, commenting, or simply following the journey. Your encouragement means the world.

Now that we have the background of the Washington Post out of the way:

Becoming Berkshire: 1973 Part 2 Katharine Graham - Personal History

Warren Buffett's passion for newspapers began at the age of 13 when he delivered copies of the Washington Post and Times Herald at 4:30 a.m. in Washington, D.C. By 1973, Berkshire Hathaway had been involved in the newspaper industry for 6 years, following the acquisition of

Let’s proceed with Warren Buffett’s investment in the Post!

Buffett Takes a Position

1973 was a dreadful year in the markets as the Nifty Fifty began to crack. “Fund managers recoiled in horror. The "safe" stocks were falling. The Dow, which had broken above 1,000, backpedaled to 950. The broad market staggered. Wall Street, now thoroughly cured of the mania of Go-Go, retreated into a malaise. Brokerage reports dried up; analysts were sent packing. Companies that had gone public in 1969 saw their stocks fall by half.”1

The market, which Buffett had found frustrating and forced him to wind up his partnership, had turned for the worst, and "Buffett was not running like a colt!"2

Buffett was now on the offensive; early in 1973, Buffett hired Salomon Brothers to raise $20 million in senior notes at an 8% interest rate. Salomon had to persuade the lenders that the money was not for textiles but rather for Buffett. He has started to nibble on the Washington Post Co. In February, Berkshire purchased 18,600 shares at $ 27. In May, the stock fell to $23. Armed with the cheap money from Salomon, Berkshire purchased an additional 40,000 shares. As the price fell further, Buffett continued buying. In September, he bought a huge block of 87,000 shares at 20 and ^3/4ths. By October 1973, Berkshire, though unknown to the public, was the largest outside investor in the Washington Post.3

The Post was trading at $23. Wall Street brokers were buzzing about IBM - the stock had declined more than 69 points, breaking through its 200-day average; they warned that the technical breakdown was a bad omen for the rest of the market. That same month, gold broke through $100 per ounce, the Federal Reserve boosted the discount rate to 6%, and the Dow fell 18 points, its biggest loss in three years. By June, the Discount rate was raised again, and the Dow headed down even further, passing through the 900 level. And all the while, Buffett was quietly buying shares in the Washington Post. By June, he had purchased 467,150 shares at an average price of $22.75, a purchase worth $10,628,000.4

“The Post owned four television stations, Newsweek magazine, and newsprint mills. Such assets were often traded in private sales and were not hard to value. Buffett figured that they were worth $400 million. However, the stock market was valuing the entire company at $100 million. The people selling, professional fund managers, would not have disputed those numbers. Why, then, were they selling? Quite simply, they were afraid that the shares would drop further. They were afraid other people might sell. As Buffett analyzed the Post, sweetly on his lonesome, he saw it as that all too rare opportunity. Mr. Market had turned gloomy, actually, seriously depressed. In such times, stock prices bore no relation to underlying values. One simply couldn't find such a bargain in the real world.”5

Buffett would explain, "It's a lot different going out in Kalamazoo and telling whoever owns the television station out there that because the Dow is down 20 points that day, he ought to sell the station to you a lot cheaper. You get into the real world when you deal with a business. But in stocks, everyone is thinking about relative price. When we bought 8-9% of the Washington Post in one month, not one person who was selling to us was thinking he was selling us $400 million for $80 million. They were selling to us because communication stocks were going down, or other people were selling, or whatever reason. They had nonsensical reasons.6

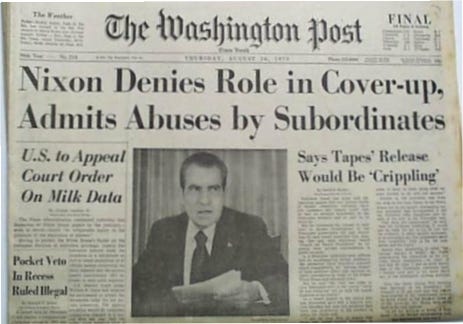

The situation was further complicated by the perception that the Washington Post was the political enemy of the Nixon administration. Nixon reportedly ordered that the Post be denied access to White House events, and advertisements connected to the administration faced pressure. In addition to attempts to discredit the newspaper, the Nixon administration even threatened the Post's broadcasting licenses through the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in an effort to apply financial pressure on the company. Clearly, there was a reason why Mr. Market was pessimistic about the stock.

Dear Mrs. Graham

Kay Graham, who took over the company with minimal business experience, relied heavily on Fritz Bebe's guidance on how to manage the organization.

"During the 12 years of his chairmanship, Fritz had a breadth of vision that included editorial as well as business judgment. He had a broad worldview, which could mean either tough‐mindedness or generosity. He could play the role of executive, but he left room for the offbeat."7

Fritz’s death in 1973 was deeply destabilizing to Kay. She felt as if she “had lost a leg.” However, luck appeared to be on her side when, about a month after Fritz's passing, Warren Buffett invested in the company. His involvement marked the beginning of a transformative period in Kay's life. Not only did it open a new chapter of learning for her, but it also sparked a friendship that has grown into something much deeper than the typical relationship between an owner and a significant shareholder.

“Warren had actually made a cameo appearance in my life in 1971, when he and his business partner, Charlie Munger, came to see me about a possible partnership to acquire The New Yorker from Peter Fleischmann. The project died, and I didn't see Warren again, or even particularly remember him, until he wrote me a letter two years later.”8

“I knew nothing about this man who had just bought a significant chunk of the company. Warren was the same person that he is now, but he was a relatively small investor at the time and mostly unknown. I knew that he had bought into the company because it fit his "rules" for investment and because our stock was so cheap: at the moment, all stocks were selling below their value, thanks to a recession, and ours was selling below other stocks, since we were relatively unknown in the business world and because of the challenges to our Florida television-station licenses - and possibly, too, because of Fritz's death and my succession.”9

“I also knew so little about the operations of the stock market that it took others to alarm me about an unknown investor buying such a big piece of the company. I had no idea about takeovers; I felt safe with the system we had in place of the family-controlled A shares as opposed to the B shares that Warren was buying. Warren assumed I felt safe and so didn't see the need to assuage any fears, but so great were the alarms that came from men around me and from the few business people I knew, including the head of Lazard, that I grew concerned about. Their message clearly was: "He means you no good."10

“I tried to find out whatever I could about this man. My research turned up only one highly flattering chapter in a book titled Supermoney by Adam Smith, which several of us at the Post read voraciously shortly after Warren's letter arrived. When I called everyone I knew who might know Warren directly or indirectly, no one I spoke to had anything but positive reactions. He had never done anything hostile; he was straight, brilliant, fine.”11

“Warren persisted in analogizing between Disney and the Post because, at the time, it looked as if no one cared about our company. He told me he had a feeling not only that Wall Street didn't see the value of the Post, but even I and the group from the Post didn't appreciate how valuable it really was. He said that someday, the market would recognize its value, although one could not predict when.”12

“He consistently renewed the promise of recognition someday by the stock market, saying that he knew it must be "discouraging to management to have poured the efforts that you have into profit improvement- with terrific results and an obvious momentum which promises more to come - only to be greeted with a big yawn in the stock market. It won't be permanent.”13

"Warren saw that I was uncomfortable with the nomenclature and language of business. He later told me that I had a kind of "priesthood approach" to business and seemed to feel that If I hadn't studied Latin and all that, I couldn't make it into the priesthood. He didn't ask me to take anything on faith, but he took out his pencil and explained things clearly. He saw that it would be helpful if we demystified a lot of what we were talking about, so he brought with him to our meeting as many annual reports as he could carry and took me through them, describing different kinds of business, illustrating his main points with real-world companies, noting why one was a good business and another bad, teaching me specifics in the process of imparting a great deal of his highly developed philosophy, He told me that, whereas Otis Chandler collected antique cars, he collected "antique financial statements.. because just as with geography or humans, it is interesting to take a snapshot of a business at widely different points in time - and reflect on what factors produced change as well as what differentiates specific pattern of development from others also observed.”14

"Buffett impressed upon me that it is better to be a bad manager of a good business than a good manager of a bad business. What Warren favors is good managers of good businesses, but I got the point."15

“One day, some weeks after we'd started my course of study, Warren mailed me the back of an annual report from the Disney Company, which pictured a child in a stroller at the end of a day at Disneyland, obviously completely wiped out, his head to one side, fast asleep. “This is you after the 10th annual report," Warren had scribbled on it.”16

“To me, Warren was a man who loved business, especially the newspaper business. I also have gotten great pleasure from his partner, Charlie Munger, who came from Omaha originally. His voice and superficial mannerisms are amazingly like Warren's. He founded the law firm of Munger, Tolles & Olson but has spent more time as an investor and as Warren's partner. To the intense amusement of both of them, I was an enduring and pleasing impression on Charlie by solemnly taking notes, like a schoolgirl at the feet of the great professor, when I went to him to talk to him about investments. One of Charlie's typical bons mots is his saying that he frequently reminds Warren "that the minimum risk we face as we scabble on it not going broke but going crazy.""17

When Harry Met Sally

“Kay was used to traveling in highfalutin circles. She thought there was one right way to dress and eat. Warren violated many of Kay’s standards; he wore a suit that looked tailored for some other man, the hair no longer crew-cut, and he came across as a corn-fed midwestern.” 18

Buffett recalls his first dinner party:

“Susie's over there sitting next to some senator. And he's trying to make out with her; he's got his hand on her leg and all these things. But I'm dying because I don't know what to talk to these people about. Barbra Bush could not have been nicer. She could see how ill at ease I was. Kay stood up and read an articulate, witty, polished, personal, and original toast to her guest of honor that she had obviously put considerable thought into writing. The guest of honor was supposed to stand and toast his hostess in kind. I didn't have the nerve to stand up and offer a toast, which you're supposed to do. I blew it. I was so uncomfortable. I even thought I might throw up. Actually, I could not stand up there in front of half the cabinet and talk. I wasn't up to it. This Senator was still trying to impress Susie and was concentrating on explaining how she should come down to the Senate and see his office. As we were leaving, he opened the door to a closet and walked through it. That was my introduction to Washinton."19

Analysis

Buffett purchased several securities in 1973, but why did it establish such a large position in the Post?

For one thing, the stock was attractively priced based on its valuation. The company had an approximate market cap of $80 million. Its net income rose from $1.52 per share to $2.08 per share in 1972, with total assets of $161 million, equity of $79 million, and only $35 million in long-term debt, indicating a strong financial position. Additionally, the company maintained over $10 million in cash. With a return on equity of 12.3%, it demonstrated robust performance, especially considering its conservative financial structure. Buffett favored businesses that could grow their capital without requiring constant reinvestment to remain viable, and the Post exemplified this quality.

The company was trading at a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 11, with 1x book value and 4x cash flow; this was certainly to Buffett's liking. Moreover, the Post was able to increase prices relatively easily, thereby generating above-average returns on invested capital.

The cessation of publication by the Washington Daily News strengthened the Post's market position. By the end of 1972, the Post accounted for nearly 63% of all advertising linage among metropolitan papers. This marked the best year in the Post's history, with a 6.5 million-line increase, bringing the total to nearly 79 million.20 This achievement positioned the paper fifth in advertising linage among all newspapers in the country.

Daily circulation climbed 6,000 to 516,000, while Sunday circulation rose 15,000 to 686,000. In the nation’s most affluent and best-educated market, 3 out of 5 adults read the Post.21

The Post was a trusted institution, although the Nixon administration may not have viewed it that way. Buffett recognized that the name carried significant weight with both readers and advertisers.

This investment had similarities to American Express and See's Candies. All three had strong brand names with a competitive moat that granted them pricing power. Buffett viewed American Express’ franchise value as an intangible asset not reflected on the balance sheet and has once stated the following about the qualitative factors of a company.

Interestingly enough, although I consider myself to be primarily in the quantitative school (and as I write this no one has come back from recess - I may be the only one left in the class), the really sensational ideas I have had over the years have been heavily weighted toward the qualitative side where I have had a "high-probability insight". This is what causes the cash register to really sing. However, it is an infrequent occurrence, as insights usually are, and, of course, no insight is required on the quantitative side - the figures should hit you over the head with a baseball bat. So the really big money tends to be made by investors who are right on qualitative decisions but, at least in my opinion, the more sure money tends to be made on the obvious quantitative decisions.22

The Post, See’s, and American Express also generated strong free cash flow without consuming excessive capital. Buffett trusted the management teams of all three companies. Like American Express, the Post was mispriced due to external factors that were not directly related to the business's competitive position. In this case, the influencing factors were the Nixon administration and an overall recession. The Post was a wonderful business, had excellent management, and was available at a fair price.

Becoming Berkshire 1930-1973:

Issue 24| 1973 Part 2 Katharine Graham - Personal History

Issue 23| 1973 Mr. Buffett Goes to Washington

Issue 22| 1972 Part 2 -The Nifty Fifty

Issue 21| 1972 - See's Candies

Issue 20| 1971 Part 3- The Nixon Shock

Issue 19| 1971 Part 2- Supermoney

Issue 18| 1971 Part 1- The Dean & The Disciple

Issue 17| 1970 Part 2 - Blue Chip Stamps

Issue 15| The Go-Go Years of the 60s

Issue 14| 1969- Part 2 Illinois National Bank

Issue 13| 1969 - Part 1 Buffett Retires

Issue 12| 1968 - Sun Newspaper & Blacker Printing Company

Sabre Arc Portfolio Updates:

March 2025 Review: $1,174,370.03

December 2024 Review: $1,209,486.84

November 2024 Review: $1,214,498.45

October 2024 Review: $1,132,767

September 2024 Review: $1,137,009

August 2024 Review: $1,094,182

Lowenstein, Roger. Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist. (New York: Random House, 1995). Pg. 148.

Id.

Lowenstein, Roger. Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist. (New York: Random House, 1995). Pg. 151.

Hagstrom, Robert G. The Warren Buffett Way (New Jersey: Wiley, 2014.) Pg. 74.

Lowenstein, Roger. Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist. (New York: Random House, 1995). 152.

Id.

Katharine Graham

Graham, Katharine. Personal History (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1997) Pg. 511.

Graham, Katharine. Personal History (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1997) Pg. 513.

Id.

Id.

Graham, Katharine. Personal History (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1997) Pg. 514.

Graham, Katharine. Personal History (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1997) Pg. 515.

Graham, Katharine. Personal History (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1997) Pg. 533.

Graham, Katharine. Personal History (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1997) Pg. 534.

Id.

Graham, Katharine. Personal History (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1997) Pg. 535.

Schroeder, Alice. The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life. (New York: Bantam, 2008), Pg. 329.

Schroeder, Alice. The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life. (New York: Bantam, 2008), Pg. 333.

Newspaper advertising linage refers to the measurement of print advertising space within a newspaper. It is typically defined by the number of lines of text in a column. This method helps newspapers track and analyze advertising volumes, which are crucial for their revenue.

1972 Washington Post Annual Report.

1967 Buffett Limited Partnership Letter